History of film music

The following research has been awarded by the french magazine "DIAPASON" as one of the top 10 internet resources regarding film music, worldwide, in November 1998.It's been translated in Greek, Italian and French and it is used as reference in the Film Music Departments of University of Pensylvania (USA), University of Sao Paolo (Brazil) and Laval University (Canada)

History of music in the Silent and Early Sound Movies

|

|

Long before the dawn of civilisation, people had discovered the power and the necessity of the addition of sound in a performance. No magician-doctor would cure a patient simply by looking silently at the stars and no headman of tribe would bring the rain merely by looking at the sky. On the contrary, they were sounding rattles, they were dancing, shouting and singing. Because even those people knew, instinctively of course, that the sound, when it is combined with pictures, imposes a psychological state on the receiver which helps him deeper believe or better understand what is happening around him. The combination of sound (music, speech, sound effects) and pictures has created throughout the centuries an amazing kaleidoscope of art forms, the major representative being - as far as live performances are concerned - the theatre. |

Even sound effects are rooted in ancient times. Inscriptions of the ancient greek period describe a method for the reproduction of the sound of thunder in tragedies. Similar methods have been used in the Elizabethan productions of Shakespeares plays and in the Japanese theatre Kabuki.

Music, on the other hand, has been established in the theatre since the ancient greek period. Centuries later, the opera introduced new ways of expression, whilst giving the primary role to music and placing the speech and setting second.

From all the above, we can see that music and drama have always shared a close relationship. Thus, when the moving image was discovered and the silent movies were born, (with the discovery of the moving image and the birth of the silent movies) it would be only natural for music to be used to accompany the action and to add levels of expression to the visual part.

But, is it really so?

|

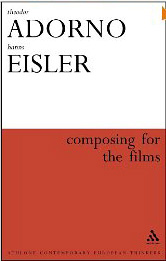

There are several theories concerning the reasons why music was chosen to accompany silent films. The first one belongs to the composer Hanns Eisler who, in his book Composing for the films, says: Ever since they were born, films have been accompanied by music. The silent picture in itself would generate a sense of ghosts, similar to the game of shadows. Besides, the shadows and the ghosts have always been correlated. |

|

The magical function of music was to soothen this sense of fear. A need was created to blunt the displeasure that the spectator felt when he saw human simulacra acting, feeling, even talking, while at the same time remaining silent.

The fact that the spectator would see dead simulacra - shadows of living people on the screen was creating the sense of ghosts; the music was introduced not to supply the characters with the life they were lacking (since this would only intensify this sense), but to exorcise the fear and to help viewers overcome the initial shock. After all, it is not accidental that silent films wouldnt use hidden actors who, in the course of the screening, would provide the dialogues, whereas instead, there would always be music which, in effect, would very often have nothing to do with what was happening on the screen.

|

|

An exception to this rule is the Italian comedian Leopoldo Fregoli who, in 1898, shot a series of comedies and who, during the screening, would stand behind the screen and act as a prompter. Also, in Japan, instead of dialogue flashcards, they would use a charismatic actor who would perform all the characters - men, women, children - would enact all the sound effects and sounds and would sing or play an instrument, thus providing the musical background. Those admirable people were called Bensi and they enjoyed such popularity, that, very often, the people would go to the cinema just for them, regardless of which film was on. Unfortunatelly, the discovery of speaking films led to a progressive disappearance of the Bensi art.

An other point view comes from Kurt London who, in his book Film Music, says that the use of music in the cinema does not derive from any artistic or psychological need, but from purely practical reasons and, more specifically, from the bad acoustic conditions of the screening. He specifically states that the projectors at the time were so noisy that a need was created for their noise to be covered by something pleasant; the owners of the theatres instinctively chose music as the most suitable solution.

|

The most interesting observation, however, comes from London who notes that:

In my opinion, of all the above stated theories, the last one touches more the unique relationship between the silent movies and music.

The first known use of music on the cinema occured on the 28th December 1895, when the Lumiere family tested the commercial value of their first films. The screening took place at the Grand Cafe in Boulevard de Capucines, in Paris, and was accompanied by a piano.

At this point, we must make a note, namely that, when we talk about music in silent films, we obviously talk about a live performance which occurs during the screening. What is more, most of the times, there wasnt even a set music. For this reason, a pianist with a great capacity for improvisation was invaluable.

The first presentation of the Lumiere programme in England took place on the 20th February1896. By April of the same year, orchestras would accompany films in several London theatres.

During the first years of commercial cinema the music material used consisted of almost anything that was available at the time and, most of the times, it would bare very litle - if any - relation to the on-screen action. The music pieces that were performed were selected by the owner of the theatre and the conductor of the orchestra.

|

While the cinema was discovering its potential, a desire was born on the part of the most sensitive producers to provide each film with its own music. This idea was materialised for the first time in 1908, when the French company Le Film dArt encouraged famous actors to make into film some of the most known works in their repertoire. The Comedie Francaise and the Academie Francaise supported this idea and together they started the production of the film LAssassinat du Dur de Guise. However, the most important incident was that the known composer Camille Saint Saens composed music especially for the film. This music was later converted into the Concerto Opus128 for strings, piano and harmonium. For various reasons, however, one of which was the additional cost, this idea was not generally widespread. In 1909, a year after Saint Saens score, Edisons film company started distributing special suggestions on music for the films that it produced. By 1913, orchestras and theatre pianists had the opportunity to be supplied with music for specific dramatical purposes, which could be found in special catalogues. The most known example is Giuseppe Becces Kinobibliotek (or Kinothek) which was first published in Berlin in 1919. The music pieces in Becces Kinotech were registered according to their style and the sentimental load that their hearing would presumably cause, while most of them were compositions of Becce himself. |

|

Some of the categories under which the pieces were placed can be seen in the example below, which is taken from Becces book Handbook of Film Music.

DRAMATIC CLIMATE

I. CLIMAX

a) destruction

b) dramatic agitato

c) serious atmosphere

d) mysterious nature

II. TENSION MYSTERIOSO

a) night: bad disposition

b) night: threatening disposition

c) innocent agitato

d) magic - ghost

e)) something is about to happen

III. TENSION AGITATO

a) pursuit

b) flight

c) heroic battle

d) battle

e) weariness, fear

f) upset masses - agitation

g) hostile nature - thunderstorm - fire

IV. CLIMAX APPASSIONATO

a) desperation - despair

b) lament

c) heat, upheaval

d) panegyric

e) triumphant

The above mentioned categories were subdivisions of the three main categories which were:

- Nature

- State and Society

- Church and State

Yet, the most crude form of the idea of musical categorisation and music catalogues was materialised by Max Winkler. Winkler thought that within classical music there is such an abundance of pieces that, should they be divided in categories in proportion to the, by now famous, Becces Kinothek, there would practically be music ready for whichever scene of whatever film. This idea appealed to the director of Universal film company at the time, Paul Gulick, who hired Winkler. So, Winkler watched these films before they were distributed, provided the theatre with a catalogue of classical extracts and instructions about the scenes over which they would be played. Thus, works by Beethoven, Mozart, Grieg, J.S. Bach, Verdi, Bizet, Tchaikovsky, Wagner and, in general, anything that wasnt protected by copyright were literally massacred.

Winkler himself reports that:

J.S. Bachs immortal chorales became Adagio Lamentoso for sad scenes. Parts of great symphonies were cut and appeared as Sinister Materioso by Beethoven, or Strange Moderato by Tchaikovsky. Wagners and Mendelssohns wedding marches were used for weddings, rows between husbands and wives and divorce scenes. If they were used for the ending, their tempo would become higher, so that they would give the sense of a happy end. Meyerbeers Coronation March was slowed down so much that it would provide a pompous musical background for the condemned to death prisoners.

Luckily, Winklers luck and his idea didnt last long

While the cinemas popularity grew, the size of the orchestra that accompanied the films during their screening grew accordingly. Thus, the institution of a music director (music illustrator), who was also the director of the theatre orchestra, was created. After having watched the film, he would choose the music, find the scenes where it would be heard and composed small bridges between pieces, so that the music would have a rudimentary unity.

However, the juxtaposition of different music pieces in a film created this aesthetic problem. Silent films did not require a stict musical translation of all scenes, but the exact opposite: the musical simplification of the cinematic pictures mosaic in a constant flow. The cinematic demand was a variety in pictures and a consistency in music. Thus, the collage of music pieces, no matter how much these bridges composed by the music director would smoothen the heterogenuity, would, in effect, do anything but be of service to the cinematic aesthetics.

The solution to all the above mentioned problems obviously lies in the composition of a separate piece of music for every film. However, as simple as this may sound, silent films would present a number of problems other than the cost of a separate composition. The main one was that of the synchronicity of picture and sound. While a pianist could easily watch the film and improvise, this was naturally impossible for a whole orchestra. A variety of devices were invented, still, none of them was considered successful. The important thing was, however, that the march towards the incorporation of a musical composition in the film production process had begun.

| Despite the synchronicity problems, there were certain films in which the music was quite worth noting. The music for D.W. Griffiths film The Birth of a Nation presents a special interest. It consists of a collage of parts taken from Liszts, Verdis, Beethovens, Wagners and Tchaikovskys compositions, as well as well known traditional U.S. songs (Dixie, The Star-Sprangled Banner). Although the films score does not have a particular musical value, it has set the standards in the orchestration and cuing techniques, which remained throughout the silent movies period. The music of the film was the product of a collaboration between D.W. Griffith himself - who, besides being a director, had also studied composition - and the composer Joseph Carl Briel. The films premiere was at the Liberty Theater in New York, in March 1915. |

|

Yet, the most important composer of the silent movies was the German Edmund Meisel, who wrote the music for Sergei Eisenstein's films Potemkin and October.

|

|

Meisels original scores for Potemkin had been lost, but they were recently refound in Eisensteins archives in Leningrand, by Jay Levda

Meisels music was neither the first nor the only one that was ever written for Potemkin. In the films premiere in Russia, in 1925, Yuri Faier is believed to have composed the instumental accompaniment, while, in 1951, Nikolai Kryukov provided the film with an other music.

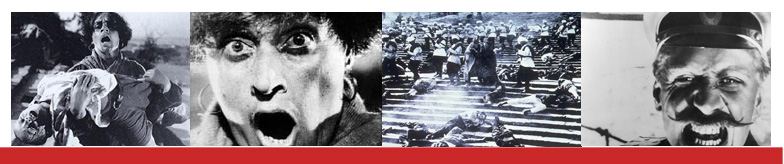

The film depicts the mutany on the battleship Potemkin during the unsuccessful Russian revolution in 1905 and was structured in five main units.

Description of the horrible circumstances on board, which constituted the cause of the mutany, the mutany itself, the support given by the people in Odyssos, the bloody attack of the Tzars Cozaks (the famous secans of the Odyssos harbour) and the final triumph of the revolutionists.

Eisenstein once said that "the sound should whip and violently shake the spectator with its tension. However, because the sound cannot be so intense, we should turn to the limits of the audiences physical and mental endurance (through music)".

Judging by purely musical creteria, Meisels music is not something memorable. Nor is there something worth mentioning, considering his composing tactics. The orchestration has been made for a medium-sized orchestra, reinforced by a full set of percussions, including two timpani, a military snare drum, a bass drum, tam-tams, castanniets, triangle, woodlocks, rattles and hooters.

What makes Meisels music special is not the means which he used but the way in which these means have created a solid dramatic structure that not only moves parallely, but actually doubles the emotional impact of the visual part. Meisel strikes at the heart of the action with every note. He provides the scene with a tormented, wild fanfare, mirrors the sailors complaint through melancholic, hostile whispers which allude to repressed rage and proceeds with the bloody collision through passages of an almost unbearable agony and violence.

|

The music, just like the film, unfolds its tension in an almost mathematical way but the result is crude, direct and instinctive. What Meisel ingeniously understood was that the music for Potemkin could not possibly constitute a mere background. It had to be transformed into an inseparable element of the film, serving and complementing the rhythm the layout and the aisthetics of the visuals. As a result, the combined power of sound and visuals remains unique and according to my opinion, there hasn't been any film in the history of cinema -even today- that managed to overcome it Meisel's technique on scoring was a little odd. He analyzed the montage of various popular silent films focusing on their rhythm, emotional climax and mood. After that, he composed a theme for each scene. Finally he compbined the different themes using the rhythm, the emotional structure and the unfolding of the visual montage as the basis for the structure and development of his music. What Meisel tried to prove was that there is a formalistic relationship between the films montage and the music. Despite all this, however, the use of this system did not necessarily mean that all good films would provide a solid music structure; most of the times, it was the exact opposite, a chaos. Yet, in other films the system would work, thus giving a specific musical unity with the music for Potemkin being the most illustrating example. |

Meisel had the luck to work with a type of director that very few composers were lucky to associate with. Eisenstein himself always considered music to be a capital factor to the creation of film. He realised that the rythm of the film was of primary importance and that was why the music and the montage had an exceptional place in his films. Even the shot or the frame had to accomodate this rythm or create conflicts that would reinforce it. The way in which Eisenstein sees films as an entity is also impressive. Thus, he differenciates himself from most of his contemporary directors and considers the shot to be the elementary unit of the cinema - as opposed to the frame which, for him, is just a photograph. A series of frames does not give birth to a shot, but instead, the shot is the smallest item, the cornerstone of a cinematic composition, while ingenuity in their combinations constitutes a montage.

Of all the above Eisensteins capacity to distinuish macrostructures is made obvious and one can comprehend why this co-operation with Meisel was so fertile.

In his book Film Form Eisenstein says that music and image should function in ways of counterpoint, so that they transmit the visual and accoustic views to a common denominator. In the same book he talks about his meeting with Meisel, which took place in 1926 in Berlin, to discuss the music forPotemkin: that was my explicit demand: to reject ordinary melodies for the meeting with the troops secans and to give substance to this demand by establishing within the music, but also within the film, musical paths in the most decisive points, thus attributing a new quality to the sound structure

This way, Potemkin stylistically evaded the boundaries of silent films with a musical accompanimentand entered the sphere of a sound film where musical and accoustic images exist in a interliked unity. Precisely becuase of these elements, this scene, together with the scene of the Odessa harbour, rightfully occupy an exceptional place in the history of the cinema and provided the foundation for an esoteric substance of music composition in the movies.

It is here that the silent Potemkin gives a lesson to acoustic cinema. Namely, that for a work to be organically functional, there has to be one and only construction law, which should govern not just every one of its elements separately, but the work as a whole.

Besides Edmund Meisel, however, there were other known composers who wrote music during the silent movies era. Arthur Honegger composed music for Abel Gances films La roue and Napoleon.

Darius Milhaud composed music for Marcel l Herbiers LInhumaine, and Dmitri Shostakovitch for the Russian film The New Babylon.

Yet, although the above mentioned films were very important, they were still the exception, since most of the theatres would use the various methods described above (classical pieces, Kinothek etc.) for the discovery and execution of music during the screenings. For the smaller theatres who had neither the money nor the room for an orchestra, various machines were invented that could be used to replace them. These machines first appeared in the market in 1910 and had manes such as One Man Pictures Orchestra, filmplayer, Movieodeon and Pipe-Organ Orchestra. Apart from music, these machines provided a series of sound effects and their size ranged from a piano with a small set of various percussions, to complex machines similar in size to a twenty-piece orchestra. Samuel A. Peeples, in an article in Films in Review magazine, describes one of these devices:

|

The greatest achievement of the American Photoplayer Company was the Fotoplayer Style 50 product, of which only one still exists today, in such a state that allows it to function. One of the best automatic musical instruments that were ever made, the Fotoplayer Style 50 was 21 feet (7 meters) long, 5 feet (1,65 meters) wide and 5 feet 2 (1,70 meters) tall. It had the capacity to reproduce the mass of a twenty-piece orchestra, plus a full size harmonium and an incredible collection of sound effects, like cow mewing, the sound of horse hoofs, some horn variations, sounds of traffic, sounds of burning wood, brushing sounds, guns, pistols and machine guns, even the sound of a 75ml French canon! One really wonders what kind of genius the user of such a monster would be. |

In addition, music played yet another important role during the silent movies period; to create inspiration during the filming. It was very common to have musicians who played for the great stars of the time when the they had to film a difficult scene. This psychological doping of the actors was applied for the first time in 1913 by D.W. Griffith during the filming of the film Judith of Bethulia, even though this music wasnt used later - which is only natural, since there was no way to record it on film. Many times they would use records instead of live music, but in both cases the music would serve the same purpose (to inspire the actor and nothing more). This music was usually muffled, quiet, and the musicians were replaced by records.

The arrival of sound put an end to all these, but generated many other completely different problems to film composers. These problems had little to do with film music itself during the first talkies.

|

Initial release 1997 Revised: June, 2013. |

|